The Pope and the Revolutions: the Papacy's evolution in the 19th century

The 19th century is generally known as an age of revolutions and liberalism. It was, indeed, a century of great changes – political, social and cultural – in the European world and beyond. Many are familiar, in general, with the evolution of the greater European countries in this age, but we tend to talk less of an important political actor who, despite the fact it had long lost its once preeminent position in Europe, still had the power to influence millions of people. We’re talking, of course, of the Papacy.

How did the Pope react to the great changes of the century and what was his attitude towards these? Did the Papacy reach a balance between its innate conservatism and the pressures of the modern world?

In 1831 – that is, a year after the revolutionary actions in France, Belgium and Poland – Gregory XVI becomes pope in Rome. Today, he is considered the most intransigent and relentless pope of the century. His ultra-conservatism meant that the Papacy would adopt a firm stance against the democratic trends and reforms both in Europe and the Papal States. His successor, Pius IX (1846-1872, the Catholic Church’s longest papacy), comes to power with a better, more liberal reputation than Gregory’s. However, if Pius IX had indeed been more open-minded towards the age’s political trends, the complicated situation in Italy would force him to change his attitude entirely and adopt a more conservative policy.

Pius IX, between liberalism and conservatism

Right after being elected Pope, Pius IX would take measures towards the modernization of the Papal States’ administration, adopting a Constitution. Moreover, he seemed to be quite favourable to the idea of an Italian unified state. The obvious question is:what triggered the change?

At the end of the 1840s, the ambitious King Charles Albert of Piedmont-Sardinia wanted to lead a war for the liberation of Italy from under Austrian control. At first, volunteers from the Papal States fought in this war with the Pope’s approval. However, Pius IX would change his mind and decide to stop fighting against the Habsburg Empire, a large catholic state and a very old ally of the Papacy. This is why Pius would forbid his volunteers to continue fighting alongside Piedmont, a decision that actually meant the Papacy officially disavowed the Italian national movement.

As such, the Pope would be highly criticized by the Italian nationalists and he would become their number one target during the 1848 Revolutions, when Mazzini’s radical group proclaimed a Republic of Rome and forced the Pope into a temporary exile.

In the matter of foreign affairs, Pius IX continued the traditional policy of negotiating concordats with Europe’s largest catholic states (Spain in 1851, Austria in 1855) and he supported the process of liturgical unification around Rome. So, in the 1840s, the Papacy re-launches an old practice:the Ad limina apostolorumvisits to Rome made by from all catholic countries/regions every five years. The visits were nothing more than a way to maintain a firm connection between Rome and the catholic national churches;it was, in a way, an instrument of centralization.

The ultramontanism philosophy, arguing for a centralization of the Catholic Church and an unconditioned fidelity towards the Pope, developed in France in the beginning of the 19thcentury.

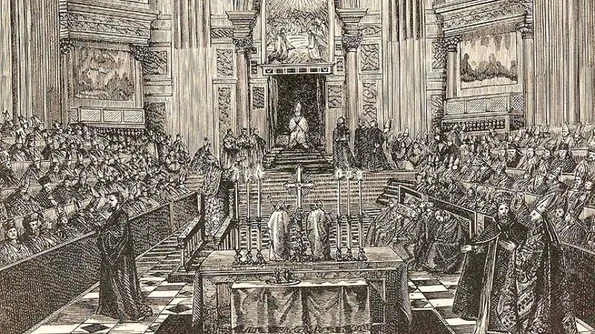

With the same centralization in mind, the Papacy started organising, for different important events, large reunions of catholic priests and bishops. The first such gathering took place in 1854, when the Dogma of Immaculate Conception was proclaimed. Then, in 1867, more than 14.000 catholic priests celebrated in Rome the anniversary of 1800 years since the martyrdom of Saints Peter and Paul.

The Vatican Council and the dogma of papal infallibility

The 1860s were a hard time for the Pope, a time of a deep crisis, having already lost the Papal States in favour of the Italian national movement. In order to compensate for the loss of Rome and his statute of temporal sovereign, Pius IX called for a new Council, organised in Rome in 1869. It was the first council of the Church in 300 years:the last one had taken place in Trent, in 1545-1563.

The Vatican Council (known today as the First Vatican Council) was held in a time the Papacy considered to be downright dangerous, because of the liberal currents hostile to the Church. In order to not lose the political battle, the Pope issued an Encyclical (Quanta Cura) dictating the ideological behaviour of all Catholics;the encyclical also included a Syllabus of Errors, condemning modern political ideologies and more:

· pantheism, naturalism, and absolute rationalism, Propositions 1–7;

· moderate rationalism, Propositions 8–14;

· indifferentism and latitudinarianism, Propositions 15–18;

· socialism, communism, secret societies, Bible societies, and liberal clerical societies, a general condemnation;

· the church and its rights, Propositions 19–38 (defending temporal power in the Papal States, which were overthrown six years later);

· civil society and its relationship to the church, Propositions 39–55;

· natural and Christian ethics, Propositions 56–64;

· Christian marriage, Propositions 65–74;

· the civil power of the sovereign Pontiff in the Papal States, Propositions 75–76 and

· Modern liberalism, Propositions 77–80.

As expected, the Quanta Cura was highly criticised all over Europe. In order to reconcile the Catholic community, the French bishop Dupanloup wrote a comment on the Quanta Cura, trying to explain the Papal document and justify its contents.

The priests gathered for the First Vatican Council were divided in two groups:a majority in favor of ultramontanism and a more liberal minority that tried to maintain the Council’s primacy when dealing with dogma issues.

The Council would adopt the Pastor Aeternus Encyclical, proclaiming the famous dogma of papal infallibility. This meant that the Pope had the right to decide in matters of dogma without being obliged to take into consideration other expertise. For Pius IX, this was a way to obtain a stronger position in front of the Council, thus compensating the loss of political power with the gain of a stronger spiritual authority.

After the birth of the unified Italian state and later on, in the first part of the 20thcentury, the relationship between the Papacy and the new political power in Italy would remain tense. It would be the mission of Pius’s successors to find a balance between the traditional catholic conservatism and the need to accept the modern world’s changes and demands, and to find solutions for coexisting with a state that led, more than once, a firm anticlerical policy.