„100th anniversary of Radu Florescu’s birth”

Comments by John M. Florescu, Second son of Professor Florescu, on the occasion of the Centenary of Prof. Radu R. Florescu, October 23, 2025, Romanian Academy Library, Ion Heliade Rădulescu Amphitheater:

My father was born only three blocks from here 100 years ago today in their beautiful home that was mostly downed by the earthquake of 1977 and then wiped clean by the construction of a subway line in the Ceausescu era.

My father’s father was a notable diplomat, his grandfather, a wealthy industrialist and Senator; his ancestors, land-owning boyars, who bequeathed lands to the oldest monasteries as far away as Tismana, Cozia and some five monasteries that grace the beautiful country of Romania.

I am honored that you, Mr. President, Ioan Aurel Pop welcome us here; President Constinescu, so admired in my country as the first truly democratic leader; and to the many colleagues here who pay him tribute. My father would be so happy to see you here today, and we thank you from the bottom of our heart. Ninety percent of his friends are gone and yet this room is almost full.

I also welcome Matei Cazacu, Constantin Giurescu’s most brilliant student, who has advised all my films in Romania. And the remarks of historian Paul Michelson from Indiana. Unfortunately, Georgeta Filitti, academician, was taken ill.

My father was baptized twice -once as an Orthodox, a second time as a Catholic. His mother was born of Hungarian blood. He was born into wealth and a family that could trace back 700 years – Indeed, the Florescu line was assured by a “Marie the Old,” who lived to 104.

Five languages and good manners were the tasks set by tutors at an early age. And also, Christian religion. Weekends were in Copaceni in a large manor house, next to Queen Marie’s “conac,” and winter holidays in Poiana Brasov, the second of two houses built in Poiana. My grandfather chose to keep his distance from the intrigues of Sinaia’s court life.

A bit like King Michael, my father was British – sense of humor, clothes, manners, fair play and dress…, you get the idea. He had a fondness for eccentrics, and for inviting scores of Romanian professors, often hungry, for dinner at 2-hour notice for my mother to cook. “Non, pas encore les Roumains!” … but she did it loyally for decades.

He survived life’s hardships of the 20th century – exile, contact with his grandparents, uncles, aunts, cousins, all possessions and the country he loved. Indeed, his father Radu ordered his 13-year-old son to board the last West-bound Orient Express to reunite with brother, sister, mother, and father, the Minister at the Romanian Legation, in London. All this just weeks before Hitler’s tanks divided Europe.

A diplomat’s son, he would see with his own eyes the personalities of WW 2: the Görings in Berlin, Roosevelt in Washington D.C. and Churchill in London. As a boy, the 7-year would dress up Romanian “cojoc” on National Day – as photographed by the Washington Post.

Events of WW2, the rise of General Antonescu would strip him and his parents of all material advantage. A telegram arrived in London from Grandemere Nathalie in 1941: “You have lost everything. We need a lawyer.”

Dad’s hardships were mild compared to those stuck behind in communist Romania, including our relatives, here in this room.

For him, no Iron Curtain - only good fortune laid around the corner. He would be educated by the finest scholars at Oxford, such as William Deakin, Churchill’s biographer, and Professor Seton-Watson, author of “History of the Romanians.”

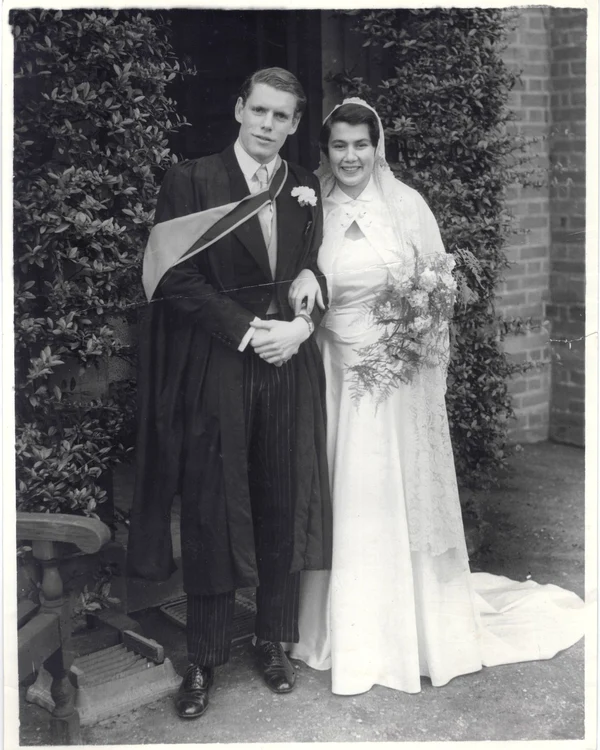

Degree in hand, and French wife, Nicole, by his side, he would board an ocean steamer with 600 pounds in his pocket. The 2-week trip to Texas delivered the 25-year-old stateless citizen to America’s most famous Balkan scholar Thad Riker.

A sea change, no doubt, from Oxford to Austin, Texas. Imagine Radu: his warm English tweeds in Texas’s boiling humidity. He adopted the ways of an immigrant with American-style optimism. A simple apartment, a simple car, a Rambler, a simple side job selling vacuum cleaners for extra money. He even watched American football.

In Texas, the couple had a friend called Lulu Baret. She was close to the powerful U.S Speaker of the House of Representatives, Sam Rayburn. To get citizenship, Lulu made the case for the new couple. The Speaker was a man of few words, “I don’t know a thing in the world about the Florescus, but if you say they’re alright, I know they are alright.” An act of Congress was quickly passed to grant citizenship.

The couple would drive north to Indiana and 100 miles east to Boston College where my father got his first teaching job. Three children were to follow Nick- myself, Radu and Sandra.

Dad would not lecture us or moralize us and rarely punish us. He didn’t have to. We never wanted to disappoint. He was positive. Even after 30 years when in 1967 he returned to Romania for the first time, he held no bitterness for communist officials who lived in his houses. I remember standing in front of the gates in Poiana. Things would get better.

In 1972, he and his colleague Professor Ray McNally seized the public stage by writing a book introducing the historical Dracula -Vlad Țepes - to the world.

While researching his book, I was his wing man, at the wheel of our Peugeot. We drove to archives and monasteries across Europe: St Gallen, Ambras Castle, Snagov, Poienari, the Vatican archives. My job was to drive the car, change tires and take pictures. It was fun.

His book became a best-seller all over the world. Johnny Carson, America’s most famous TV man, and David Frost introduced him to tens of millions. By this time, the Professor warmed to fame but he was not always an obliging candidate. He told Carson’s producer that he would accept the invitation only if he could have 2 minutes to “speak seriously” about Romanian history.

His “Dracula” book drew an odd set of admirers: Jean Marais, the French actor, Mother Theresa, Prince Philip and Yehudi Menuhin. Wanting to escape the label of being “the Dracula professor,” he pointed his other non-Dracula books and 60 academic articles.

My father’s rise in the United States allowed him to play a new role in American life – as a quasi-diplomat helping Romania. He explained to us: “Romania has had many kinds of leaders – medieval princes, boyars, foreign royalty, fascists, communists and post communists. Truth is Romania has a small voice in America… we should try to be at its service as best we can.”

Dad worked discretely from the sidelines. When President Nixon came to Romania in 1969, Dad and I were at the airport. At a reception that night, President Nixon asked, “What are you doing in Romania?” “I am writing a book on a Romanian Prince.” Nixon was perplexed.

My father was close to our Senator Kennedy, the president’s brother known as the “Lion of the Senate.” He pushed our Senators and Congressmen to support “Most Favored Nation” status for Romania.

Mircea Geoana, the Foreign Secretary, named him Honorary Consul in Boston in 1996, and also named my brother, Nick, in Houston where he serves today.

On the occasion of Romania’s entry into NATO, in 2004, my father was on the south lawn of the White House with President Bush. After the 1989 revolution, Dad read on national TV an open letter from Senator Kennedy to the people of Romania. He journeyed with a number of Congressmen and U.S. diplomats to Romania. And in the opposite direction, from Romania to Boston, he’d invite Romanian presidents (Constantinescu and Iliescu), Princess Margaret, dignitaries, scholars and artists.

You probably figured out by now that my father had all kinds of friends. Powerful, those on the sidelines, those from afar, those in need or not. He was open to all kinds. He cared for them and they cared for him. He impacted their lives without expecting anything back. He did things with grace, sustained by loyalty.

The happiest day of his life would be right here at the Romanian Academy, when in 2000 he was honored with “Diploma Honoris Causa” by Academy President Eugen Simion. He said it himself right here: “When I was detached from my country, I dedicated myself to Romanian history in order to find a link with my country.”

Within one hour of his death, we gathered around his bed in Mougins, France. Looking right at us, he gave us five duties: Look after your mother. Look after my sister. Keep united as a family. Look after Romania – and he did not mean our businesses. And take care of my books.

Days later, a note arrived from King Michael of Romania, capturing his essence: “He took a drop of Romanian history and universalized it for students around the world.”

Thank you.

Pictured above: Radu R. Florescu with his sons Nick and John (© Florescu family archive)