Young Stalin, an Al Capone of the Caucasus

All his life, right until his sudden death in March 1953, Stalin was extremely careful in putting a stop to any attempt of researching, documenting and publishing his youth’s biography, because it would have damaged his later official biography. As such, Sebag Montefiore’s book, published by McArthur &Company in Toronto and bearing the title Young Stalin, is a worldwide premiere because it describes, in great detail, how the Georgian Osip Dzhugashvili, of Ossetia, became the Soviet dictator Joseph Vissaronovici Stalin.

All the books about Stalin that have been published until today hardly relate his youth years spend in Georgia. The present book presents, in its 442 pages, only Osip’s young years spent in the Caucasus, before his self-imposed exile in the Russian Empire. Sebag Montefiore has become, incontestably, Stalin’s best documented Western biographer. This fact has been confirmed by known writers such as university professor Robert Service, of England, or American researcher Robert Conquest, both of whom have dedicated their lives to researching the USSR’s history.

The first surprise this book brings is the completely new information that makes this biography an absolute worldwide premiere. People have been wondering where the author gathered so many intimate details and one-of-a-kind photographs. The answer lies in the last six pages of the books, filled with hundreds of names of people all around the world who have given him information and photos dating from Osip Dzhugashvili’s youth. The first to do so were Sandra and Mikhail Saakashvili, the presidential couple of Georgia.

The author writes that the Georgian president has given a presidential decree in order to allow him access to Georgia’s secret archives. Even more useful was the invitation made to the Georgians themselves, by national television, that the people in possession of new details, intimate diaries or unpublished memoires of people that had met or worked with Stalin bring these forth to the presidential Chancellery, who promised to guarantee their anonymity, if requested.

A simple gangster

It is obvious the book’s author has greatly benefited from the help and friendship of Georgia’s presidential family in collecting so many information regarding Stalin’s youth in Georgia. A reader with enough patience and curiosity to methodically read the last six pages of the book will be amazed. He will find not only Georgian and Russian names, but names from all over the world, of people who have proudly kept, from their grandparents, photos or journals or unpublished notes attesting to their direct participation to Georgia’s Stalinist history, and who have met Osip Dzhugashvili before he changed his name to Stalin.

Western historians will find here some explanations regarding Winston Churchill’s words:‘Stalin came to Russia with a wooden plough and left it in possession of atomic weapons’. So, in 29 years, this man from Georgia managed to transform Russia into a worldwide superpower, something the Americans did in 200 years with more than 30 presidents.

The book’s second surprise is that it reveals young Stalin’s biggest secret, guarded so fiercely by the dictator himself and his successors:before becoming a political leader, Osip Dzhugashvili was nothing more than a gangster, a common law criminal, with multiple arrests in his native Georgia, a bank robber and a qualified crook.

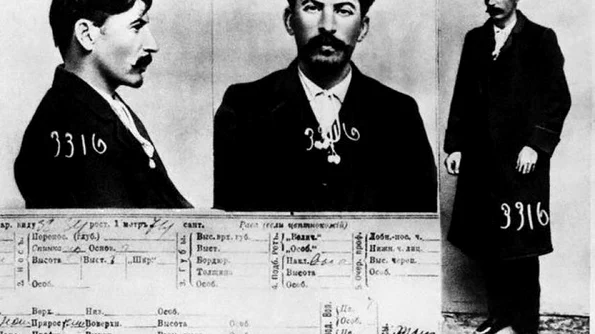

He began by extorting money from patrons in the Caucasus, as ‘protection tax’. People who refused to pay first received a warning, through fires set by Dzhugashvili on their properties, causing greater financial damage than the initial money requested. This first warning was followed by kidnappings. For example, the Rothschild Barron, who had an oil business in the Caucasus, had an employee whose sole job was making sure the money payments to Dzhugashvili were made on time. The book contains photos of Osil Dzhugashvili in the police headquarters in Tiflis (today’s Tbilisi), elegantly dressed, just like Chicago’s Al Capone.

Childhood beatings

At the age of 80, Stalin’s mother, Keke Dzhugashvili, wrote (in memories still unpublished) that her son Osip had suffered, when he was six, two accidents that would make him a cripple for the rest of his life. For example, with his left hand, which was shorter than his right one, he couldn’t even hold a cup of tea. [..]

The author also talks about the other inferiority complexes Stalin had throughout his life:missing toes on a foot, which disqualified him from the military service;the scarred face, caused by small;and, most importantly, the persistent rumors he was in fact a bastard of a local nobleman, Koba Egnatashili, whose photo appears in the book. Besides being physically invalid, the book also shows Stalin had psychic damage cause by his parents. According to eyewitness accounts, at his last meeting with his mother Keke, in the 1930s, Stalin asked her why she used to beat him savagely as a child, to which Keke responded ‘If I hadn’t, you wouldn’t be where you are today’.

From his school years at the Theological Seminar in Tiflis, Osip Dzhugashvili kept fond memories of only one professor, history teacher Makhatadze, whose life he saved in 1931, when he was imprisoned and awaiting execution. Montefiore provides the telegram sent from Moscow by Stalin to the Georgian party First-Secretary:‘Nikolai Dimitrievici Makhatadze, aged 73, is held at Metehi prison. I’ve known him from the Seminar and I don’t think he is threat to the Soviet power. Release the man and let me know.’

How Stalin was born

Montefiore has also found the source of Osip Dzhugashvili’s chosen name. Among the many lovers he had in Georgia, activist Liudmila Stal was the daughter of a steel factory owner in southern Ukraine. She was six years older than him and a veteran of Tsarist prisons. The two had an on-and-off romance because of her Parisian exile.

She worked closely with Lenin in exile and, every time he met Lenin abroad, Stalin also met with Liudmila Stal, who had an obvious influence over the young Georgian. They saw each other, for sure, in 1917. Nothing survived of their friendship, except the surprising decision that would change his life:Osip Dzhugashvili inspired his alias, Stalin, from Lidumila Stal’s name.