RUSSIA: HOLY LAND OF THE ENLIGHTENMENT Myth and Propaganda in 18th Century France

The rapid emergence of Russia as a great European power happened during a period when European enlightenment thinkers were asking themselves basic questions about the nature of society and government: what was the best form of government, autocracy or representative government? Could autocratic reforms be benevolent? Why and how had mankind transited from a state of “nature” to a state of society? What was the purpose and nature of the “social contact”?

The emergence of Russia posed a number of questions. Were the Russians Europeans or “Asiatics”? Could their form of despotic government result in enlightened reforms? Were they not lovers of liberty, like other “northerners”? How could Russian “barbarians” be civilised? Was it Russia’s destiny to become the most powerful country in Europe? Many of the leading French “philosophes” asked themselves these questions. Some kept up a lively correspondence with Catherine the Great, a fiercely intelligent woman who loved discussing ideas, but also understood the value of flattery and propaganda. A handful allowed themselves to be manipulated by her, and sometimes found inducements of money difficult to resist.

Disillusionment set in once travellers began to write about real conditions in Russia, and in particular after the 1772 Partition of Poland, when Catherine the Great annexed parts of the country, alongside Prussia and Austria.

In a letter dated 11th June 1759, Voltaire remembers having seen Peter the Great on his visit to Paris some forty years earlier, when the writer was still a young man: "When I saw him forty years ago, visiting the tradesmen of Paris, neither he nor I had any doubt that I would one day become his biographer." The youthful Voltaire, catching a glimpse of Peter, seems to have experienced a realization that one day he would become the biographer of the great Russian Tsar. À young boy who was going to become the epitome of good taste, modernity, and letters in Europe, is fascinated by a huge and strange ruler, overpowering because of his very savage barbarity, who has come all the way to Paris to be westernized and cultivated.

This meeting, whether fictional or real, can be taken as the symbolic coup de foudre of a fully-blown love affair that was to develop between the main protagonists of the French Enlightenment and Tsarist Russia. It was a love affair that began as an early and hesitant admiration, that developed into a blind affection, and that eventually underwent a phase of disillusionment.

In the early eighteenth century, little was known of Russia in France. Trade routes and contacts between the two countries had been minimal, and the earliest writings on Russia tended to be in English or German, rather than French. Peter the Great's visit to Paris obviously left its mark on the few people who met him. But most French courtiers remained hostile to the “barbaric” manners of Peter during his 1717 visit. Saint Simon was one of the few members of the court on whom Peter left a favourable impression. The visit itself did little to stimulate writings on Peter or on Russia, although a trickle started to appear. Those early French authors who dealt with the subject all stressed the barbarity of Russian civilization and of Peter himself. The ambassador Erizzo had written in 1698 on Peter, “Barbarian in his habits....he punches and kicks whoever gets close to have a look at him."

In the seventeenth century, writers in England and the German lands had been critical of political conditions in Russia. For social contract theorists such as Grotius, because a citizen of the Duchy of Muscovy was forbidden to leave its geographical confines without governmental permission, the Duchy represented a blatant negation of that theory which saw the origin of political power in a free association of individuals. In France, Huet had noted that, "[The princes of Muscovy] do not allow [their subjects] to leave their country, and they make them avoid any exchanges with foreigners." Nevertheless, Peter the Great found a precocious French admirer in Fontenelle, who was the first writer to assess the monarch's reforms against the background of previous political and cultural conditions in Russia.

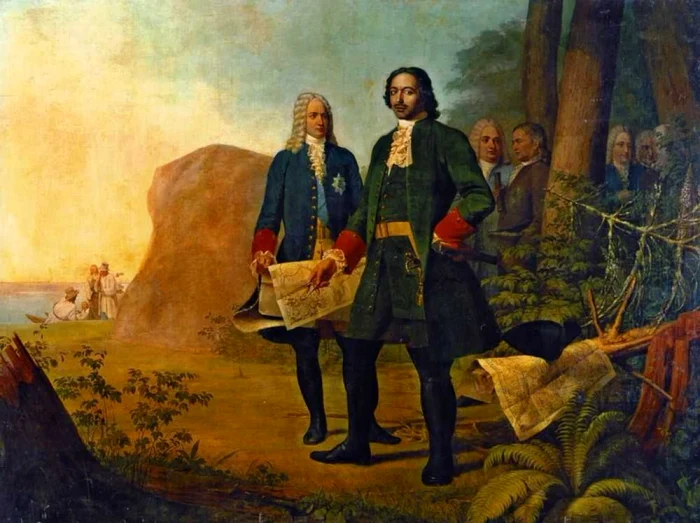

Peter the Great’s travels in Europe

Towards the end of the 17th century, not much was known about Russia in Europe. What little information was available trickled out through north European merchants active on the centuries-old Baltic Sea trade routes. This began to change with the accession of Peter the Great in 1682. A landmark in the European “discovery” of Russia (and Russia’s discovery of Europe) was his first European “grand tour” of 1697-98, when, accompanied by 250 attendants, he set off on a journey to France, Austria, and eventually the Netherlands and England to develop diplomatic relations and learn about Europe, its habits, political and financial systems, scientific discoveries and, crucially, industrial technology (shipbuilding being a key area of interest). The journey was, amongst other things, a preparation for the long “Great Northern War” with Sweden (1700-21) fought over the destiny of north east Europe. The start of the war was followed by the building of Peter’s new “European capital” of St Petersburg in 1703, with the help of European (especially Italian) architects and technicians. In 1716-1717, Peter completed a second and final European tour in 1716-1717, a few years before his death.

The philosophes’ views on Russia

The first French thinker to theorize extensively about Russia is Montesquieu. His earlier views on Russia are presented in his Persian Letters of 1721, where his attention is struck by Peter's reforms: “The Prince who presently rules has wanted to change everything; there were big fights with the Mucovites regarding their wearing of beards. Anxious and always agitated, he wanders in his vast lands, leaving everywhere signs of his natural severity. He then leaves them, as if they cannot contain him, and comes to Europe to look for other provinces and new kingdoms."

Montesquieu’s Russian paradox

Yet Montesquieu is puzzled by a paradox. He believes that the Russian people are “northerners”, and therefore “stoics and lovers of liberty”, with "few vices, quite a number of virtues, a lot of sincerity and frankness”. He also sees them as essentially European (In 1716 the Duchy of Muscovy had entered the Royal Almanach for the first time as a European power; Montesquieu never questions the correctness of this judgement). Why then had Peter's attempts at westernization needed to be imposed tyrannically, from above?

In his On the Spirit of the Laws, Montesquieu resolves this paradox by stating that Russia's despotic government and “barbaric” customs were "strangers to the climate [but] had been brought there by the mix of populations and conquests." In other words, although Peter had attempted do Europeanize Russia from above, he could have done so without recourse to despotic methods, because he was in fact simply restoring Russia’s true essential nature, which had been corrupted by the Mongol invasions. He thus sees Peter's reforms as unnatural and unnecessarily tyrannical. The example he uses is Peter's prohibition of the Russian nobility’s wearing of beards: “Every useless law is a tyrannical law: such as the law obliging the Muscovites to cut their beards." This policy of forceful Europeanization by Peter is also condemned on a theoretical basis: "There are ways to prevent crimes; it is by means of punishments; and there are ways to change habits, it is by giving examples... It is a very wrong policy to seek to change customs by issuing laws,.,.generally, people are very attached to their own customs; and to forbid them, will make them unhappy: one should not change them by decree, but encourage them to change them themselves."

Actually, Montesquieu had failed to understand the true nature of Peter's reforms, which represented an attempt to centralize power by curtailing the rights and customs of the aristocracy. On the contrary, he sees them as a move by the Russian Tsar away from despotism towards constitutional government: "Please take note of how energetically the Muscovite government is striving to escape the despotism which is heavier for it than for the people themselves."

Montesqieu’s view that Russians were “northerners” and therefore freedom lovers were based on a simplistic “geographical anthropology”, projected onto a society of which he knew virtually nothing. He never travelled to Russia and travellers’ descriptions of real conditions in the country were hardly available in France at the time he was writing.

Voltaire, fascinated by Russia’s lack of civilisation

Voltaire’s views on Russia are fundamentally different from Monstesqiueu’s. A rationalist and optimist about the perfect-ability of man and society, what fascinates him is precisely the country's lack of civilization, the fact that for him it was tabula rasa, a country with no history, no real nature prior to Peter’s reforms. His starting point is the complete backwardness of the country – the idea that Russia had never really been part of Europe.

In his History of the Russian Empire under Peter the Great, Voltaire takes great pains to describe the pre-Petrine people of Russia as complete “savages”. For Voltaire, there is no doubt that the Russians are not Europeans, but Asians: "The habits, the clothes, the customs of Russia always belonged more to Asia than to Christian Europe." Voltaire compares the “savages” of Russia with those of the New World. He writes about the Siberians descending from their lands to sell furs, "which they bartered for nails and pieces of glass, like the original savages of America and the Spanish...they live in caves, in huts amongst the snow."

For Voltaire, precisely because Russia was so bakward, there was no limit to the extent to which it could be civilized. Furthermore, Voltaire had no issue with it being civilised from above. In Voltaire’s last work on Russia, his 1768 Anecdotes on the Tsar, he summarizes this optimism with the motto, "one only has to wish, one does not wish enough." For Voltaire, a superhuman monarch was capable of moulding human nature, of creating out of nothing. In his He had claimed in his Essay on Customs that: "Almost nothing has ever been achieved except by the genius and firmness of a single man fighting the prejudices of the multitude," and that "one can do everything: the great fault of almost all who govern is that they have only half-wills and half-means."

Moreover, his view of Russia is deliberately polemical in order to advance his agenda for France. If a benevolent autocracy had worked such miracles in Russia, why could an enlightened French monarch not transform the fortunes of France? His History of the Russian Empire under Peter the Great concludes with the following appeal to enlightened Europe: “The rulers of long established countries will ask themselves: if a man, with his genius alone, can achieve so much in the icy climes of ancient Scythe, what should we do in kingdoms where the accumulated work of centuries has rendered everything so easy?

But Voltaire’s views on Russia were also subject to pressures from the Russian court. Long before writing his History of the Russian Empire under Peter the Great, Voltaire had expressed a desire to become Russia’s official historiographer. Having been refused this honour by the St Petersburg Academy (who had no wish to see a work on the delicate subject of Russian history written by a foreigner), he had to wait for the accession of the Empress Elizabeth, when her Francophile lover, Shuvalev, himself began to make approaches to Voltaire on the subject. Thus Voltaire, encouraged by the Russian court, and no longer held back by his devotion to the strongly anti-Russian Frederick the Great, began to write his great history.

However, problems soon arose between Voltaire and the Russian court on the material the writer had included in the first manuscripts of his History of the Russian Empire under Peter the Great. Firstly, Voltaire had already written about Peter the Great in his History of Charles XII. Although complimentary about the legislative work of the Tsar, he had not been entirely uncritical of Peter's motives in his wars against the Swedish Empire. This did not suit Voltaire's Russian protectors who had wanted Peter do be portrayed as an aggressed pacifist. Lomonosov, who had supplied him with most of his material for his History of the Russian Empire under Peter the Great, suggested that Voltaire author the new book under a fictitious nom de plume, to have full liberty in his portrayal of Peter, avoiding any danger of it being criticised for inconsistencies with his earlier History of Charles XII. However, Voltaire refused to become the complete tool of the Russian court, and eventually teased them by signing his new History of the Russian Empire under Peter the Great, “by the author of the History of Charles XII”.

Voltaire and the Russian Academicians

There were other conflicts between Voltaire and the Russian academics who were helping him with his history. Voltaire had wanted to stress the utter backwardness of Russia before the reign of Peter, in order to emphasize the extent of the Tsar’s achievements. The Russian authorities were unlikely to approve. Yet the real disagreement inevitably centred around the delicate question of Peter’s brutal execution of Alexis, his son and the heir to the throne.

Whilst Voltaire went as far as to justify Peter on the grounds of raison d'etat (Alexis having shown signs of supporting the reactionary and-Petrinè party at the Russian court), the Russians wanted Voltaire to accuse Alexis of an actual conspiracy against his father. This he refused to do. There was clearly a limit to how far Voltaire was prepared to bend the truth to please the Russian courtiers, if only because of the embarrassing accusations of flattery he was likely to suffer. In 1761, we find him writing on the question of the Tsar's murder of his son, "This chapter is embarrassing, as, whilst I love very much the Empress of all the Russias, I am madly in love with the truth.”

In spite of these disagreements, the Russian court was pleased with Voltaire's work, and with good reason. Russia is seen as a standard of enlightenment by which all European states should be judged. For Voltaire, eighteenth century Russia was a tolerant state: Peter and his brother Fedor “allowed everyone to serve God according to their own conscience." The Russian church was subjugated to the state: "The patriarch Adrien having died at the end of the century, Peter declared that there would not be another one to replace him." The nobility had been crushed, and “they gradually reformed the main abuse of the military, this independence of the Boyars, who could form militias made up of their peasants."

An idealized vision of Russia

Russia, according to Voltaire, had become a country governed by fixed and immutable laws, like England. Peter “enacted his new Law Code in 1722, and he forbade on penalty of death all the judges from straying from it, and of substituting their own opinions for the general law." Finally, it was a nation where the arts were flourishing, and in which the state had successfully established charitable institutions to look after the needy: “They are establishing new maths schools, which by 1716 could be found in all the cities of the Empire. Those orphanages and foundling homes which had already been started, were finalized, furnished and filled up."

How could Voltaire have failed to question such a naive and idealised view of Russia? Sheer ignorance of the country most likely played a role. Unlike Montesquieu, he had received an invitation from the Empress Elizabeth to visit the country, but had refused to travel there. But also, importantly, most of the information he had accumulated on the country had been fed to him by the Russian court itself.

Rousseau: the Russians will never be civilised

Unlike Voltaire, Rousseau did not spend much time researching Russia or engaging with its rulers, nor did he write extensively on the subject. But, like the other philosophes, he took an interest, and made a number of generalizations about the country in his On the Social Contract of 1763, without going into any detail on the actual situation in Russia. Rather, his views on Russia stem from his general views on the natural goodness of “primitive” man and the evils of civilization, views which were the opposite of those of the other philosophes, and in particular Voltaire who emphasized the perfectibility of man, including from above.

Unlike Montesquieu, but like Voltaire, Rousseau sees the Russians as fundamentally uncivilised. However, unlike either of them, he considers that Peter’s reforms failed precisely because he tried to civilise them too early. Furthermore, he considers Peter’s reforms a western import, and therefore doomed to fail: “The maturity of a people is not always easy to discern, and if one seeks to bring it about too early the work will be ruined. Some peoples can be disciplined from the start, others will still not be after ten centuries of work. The Russians will never really be disciplined, because they were disciplined too early. Peter had a genius for imitation, but lacked that real genius which can build things from scrap. He did some good things, but others were misguided. He saw that his people were barbarous, but did not realize they were not ready to be policed; he wanted to civilise them but should have focussed on making them strong. He wanted above all to make them into Germans or English, whilst first he should have formed them as Russians.”.

Rousseau contrasts the vitality and strength of Russia with the decadence of Europe, but believes that, because of Peter’s misguided reforms, Russia will itself eventually end being dominated by a fresher, less European civilization to its south and east: “The Russian Empire will strive to conquer Europe but will itself be conquered, its Tartar subjects and their neighbours will become its rulers and our masters. It seems to me that this outcome is inevitable. All the kings of Europe are working in concert to help bring it about”

But Russia was too vast for it ever to be able to conform to Rousseau’s democratic ideal of a small nation envigorated by direct citizen participation. In another passage of his Social Contract, he praises Corsica as the country with the greatest potential for development, due to its freedom-loving people and relatively small size. His views, while very influential on 19th century and early 20th century Russian thinkers, had little impact on contemporary writers in France.

Catherine the Great and the Philosophes

The same year that the Social Contract was published saw the accession to the throne of Catherine the Great, the German-born Tsarina who consciously cultivated a good image with European intellectuals. Diderot wrote of her: "I assure you that you will find her prostrated in front of the image of posterity."

Catherine did not hesitate to cultivate the admiration of these intellectuals, understanding their usefulness as a source of propaganda. More than that, she rewarded the philosophes who praised her nation and in particular her policies with material gifts, as well as flattering them with invitations to visit her and assist her in her legislation. In a letter addressed to Catherine, Voltaire writes: “All those who have been honoured by Your Majesty’s are my friends. I am grateful for what you have done so generously for Diderot, D'Alembert, and the Calas family. Every man of letters in Europe ought to be at your feet." Voltaire obviously took his gratitude to Catherine seriously, for early in 1768 he was writing to d'Argenel: “I have a favour to ask you, that is, for my Catherine. We must re-establish her reputation in Paris...l beg you, say much good of Catherine."

Her first concern regarding public opinion in Europe was the inevitable talk of the murder of her husband Peter. Pictet, Catherine's agent in Geneva, was immediately made to write to Voltaire assuring him that “You will find on the throne a true philosopher." Voltaire, perhaps hopeful that the Russian Empress would be receptive to his ideas, began to condone her role in Peter’s murder by, characteristically, assuming a humorous tone: “I confess that I fear having a corrupt enough heart not to be as scandalised as a good Christan should be. This little evil could result in great things. Providence is as the Jesuits used to be: it avails itself of all means to achieve its means." Another joke of the philosophe was that he did not wish to meddle in family matters.

Meanwhile, Catherine was already courting another philisophe, d'Alembert, offering him to become the tutor to the Grand-Duke, her son and the heir to the throne. Shortly afterwards, D'Alembert wrote to Voltaire, "I agree with you that philosophy should not be very proud to have such pupils, but what can one do? One must appreciate one’s friends in spite of their faults."

Catherine’s correspondence with Voltaire

It is in this climate that the long correspondence between Voltaire and Catherine developed. It lasted until his death in 1778. In these letters, there is a complete absence of a frank exchange of ideas between the two correspondents. Rather, the letters did not progress beyond assertions of mutual praise and flattery. The sharp disagreements which enliven Voltaire's correspondence with Frederick the Great, which are a testament to a genuine friendship and a lively exchange of ideas, are nowhere to be found in the letters between Voltaire and Catherine. The closest the two correspondents ever got to a literary discussion concerns the translation of certain French plays for the Smolny Institute, which Catherine had founded for the education of young noble girls.

Catherine the Great understood that she could influence public opinion in Europe through the prolific pen of Voltaire. She would often write to “inform” him on real conditions in Russia. Already in 1765, she was writing that, "tolerance is widespread in this Empire, only the Jesuits are not tolerated." Four years later, she wrote to Voltaire that "there is no peasant in Russia who does not eat chicken when it pleases him, and in some provinces they prefer turkey to chicken."

One of the main issues which Voltaire failed to address in his letters to Catherine was the deteriorating conditions of the Russian serfs. In 1767, the Free Economic Society of St Petersburg held a competition to which Voltaire submitted an essay criticizing the institution of serfdom. He failed to win the prize, which was awarded to another Frenchman who had written on the danger of philosophers meddling with affairs of state! Six years later, when the Pugachev revolt broke out, Voltaire failed to make any connection between the revolt and the conditions of the Russian peasantry. In his letters to Catherine during the revolt, he expressed more concern for the health and safety of the Empress than about the economic conditions underlying the revolt. It is interesting that in his ABC of 1768, in which Voltaire listed the countries where the institution of serfdom was practised, he failed to include Russia.

Voltaire also used his letters to encourage the Empress in her war against the Turks. In a letter written in September 1770, he looks forward to the moment when Russia will liberate Greece from the Turkish yoke: “They will write a Cateriniad [in your honour], the fall of the Ottoman Empire will be celebrated in Greek; Athens will become one of your capitals; the Greek language will become universal; all the merchants of the Aegean will ask you for Greek passports." And in 1772, he was yet again encouraging the Empress in her crusade against the Turks, "I will always object to any peace treaty which does not award you Istambul."

A key change in educated European opinion on Russia took place that same year, with the first Partition of Poland, whereby Russia, Prussia and Austria dismembered the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, enlarging their respective lands. This is how Catherine broke the news to Voltaire: “My domains have...grown a bit pursuant to an agreement between the court of Vienna, the King of Prussia and myself. We found no other way of protecting our borders from the incursions of the supposed [Polish] confederates commanded by French officers, other than by extending them.”

Voltaire appears to have been genuinely shocked (and hurt) by the partition of Poland, considering it a personal betrayal, as he had always supported Catherine’s interference in the affairs of Poland on the grounds that she was working for the cause of tolerance against the backward Polish nobility and the obscurantist Catholic Church. Catherine had herself assured him that this was the case. Voltaire wrote in 1772: “I was caught out like an idiot when I naively thought, before the Turkish war, that the Empress of Russia had an understanding with the King of Poland to do justice to the dissidents and establish freedom of conscience.” However, soon after the event, Voltaire was again publicly apologetic both about Catherine and the partition itself, whilst D'Alembert remarked that "philosopy...pardons the conquerors for the harm they do to their enemies, proportionately to the good they do their subjects."

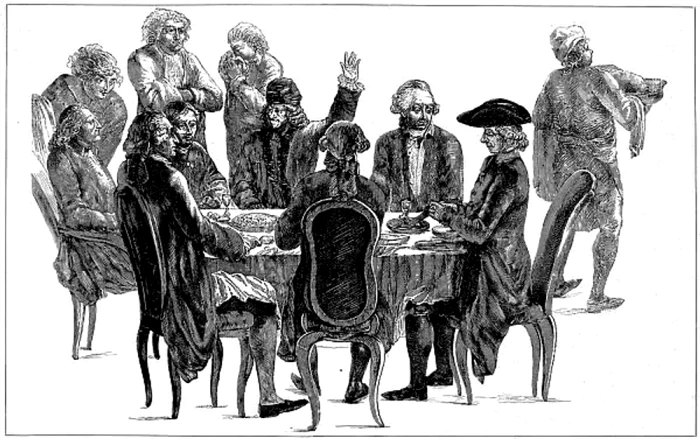

The Philosophes travel to Catherine the Great’s Court

Eventually, it was not so much the partition of Poland as the realities of life in Russia which began to puncture the writers’ positive views on Catherine, for no actual journey of a philosophe to the Russian court in St Petersburg turned out to be a success. In 1767, Le Mercier de la Riviere had been invited by Catherine to join her court as a “jurisconsult”. He arrived in St Petersburg in the Autumn of that year and left the following March without having once been consulted by the Empress or her assistants. Indeed, the Empress remained in Moscow during the entire period of his visit, and had no desire to invite the physiocrat to visit her in a city which was not as European and westernized as St Petersburg. On his return, the physiocrat remained deeply disillusioned by his Russian experience.

Similarly, in 1773 Diderot set off for St Petersburg, having finally decided to accept à long standing invitation to visit the Empress. Of all the philosophes, Diderot had undoubtedly benefited the most from Catherine’s help. She had bought his library at a moment when he was in desperate need of money in order to provide a dowry for his daughter. She had awarded him a pension for life, and had offered to assist him with the publication of his Encyclopaedia in Russia. She had also paid him as her agent to buy paintings for her collection in France (kick starting the Hermitage’s collection).

Diderot, who did not like travelling, set off for St Petersburg out of a sense of gratitude towards his benefactress. Yet his stay was by no means a success. If Diderot could write that Catherine “combined the spirit of Caesar with the charms of Cleopatra", relations between the two soured relatively quickly. Unlike le Mercier de la Riviere, Diderot was received by the Tsarina, and usually spent two hours with her every afternoon.

His disagreements with her were on matters of principle. He would not accept that Russia was a fully civilized country until Catherine transformed it into a constitutional monarchy with representative institutions. Thus, he differed completely from Voltaire, who envisaged that progress in Russia could be achieved through the benevolent despotism of an enlightened monarch. Diderot recorded his conversations with the Russian Empress in his Memoirs for Catherine II. He suggests to the Tsarina that: “All arbitrary government is bad, including the arbitrary government of a good, firm, fair and enlightened ruler. That ruler gets people into the habit of respecting power, whoever wields it. He removes from the nation the right to deliberate, to want and not to want, to oppose, even to oppose good things."

For Diderot, it was not sufficient that Catherine had summoned and consulted a legislative commission to assist her in her work. She had to make the institution permanent. In other words, he was demanding that she abdicate her absolute power. His exchanges with Catherine represent the ultimate confrontation between the idealism of the philosophes and the realities of the social and political situation in Russia. When Diderot advises Catherine, "Above all use your commission to establish this kind of equality before the law", he shows his complete ignorance of the realities of power of eighteenth century Russia, for the commission summoned by Catherine was precisely the kind of institution which would speak for the privileges of the “corporate” interests in Russia from which it was drawn. In a letter to Voltaire written at the end of 1773, Catherine could only say, "I find in this Diderot an inexhaustible imagination, and I consider him to be amongst the most extraordinary men ever to have lived.”

So whilst a mutual intellectual respect survived, their conversations became less and less political, and more and more concerned with questions of aesthetics and education. Presumably, Diderot realized that he had little hope of changing the Empress's views, and sought to avoid alienating her. His Memoirs end three months before Diderot's departure from St Petersburg, either because he no longer felt it was any use recording his conversations with the Tsarina, or because they met less and less often. By the time of Diderot’s departure, the Empress and philosophe had only agreed on the uses of education and of the fine arts, especially the theatre, for moral and political purposes.

On his return to France, Diderot wrote his Observations on the Nakaz, where he looks back with bitterness at his Russian experience: "The Empress has said nothing about liberating the serfs. Does she want her nation to continue living in slavery?' He then proceeded to strengthen the criticisms of Russia which had appeared in the first edition of Raynal's History of the two Indias, and to add new ones for the second edition. His relations with Catherine remained cordial, perhaps because the Empress only read the Observations after the philosophe's death in 1784.

Catherine herself was to die in 1796, a century after Peter the Great set off on his heroic first grand tour of Europe, a century of increasing exchanges, but also of misunderstandings and of manipulation, of optimism followed by disillusionment amongst the intellectuals of what has come to be known as the “West”.

Articolul face parte din numărul 250 al revistei Historia, disponibil la toate punctele de distribuție a presei, în perioada 15 noiembrie - 14 decembrie, și în format digital pe platforma paydemic.