A History of the Florescu’s: The Turbulent Century

After the achievement of the unification of Moldavia and Wallachia in 1859, followed by their emergence as a sovereign state in 1878, it was only natural for many Romanians to start thinking about their compatriots living under Hapsburg rule in Transylvania, the Banat and Bukovina. The situation was complicated by the position of King Carol, who was the major political force in the country throughout his reign. As a Hohenzollern, he had a natural affinity with Germany, and he was soon to be sucked into an alliance with Germany and Austria which was to last the length of his reign, making any direct confrontation with Austria impossible. Although he managed to get a number of leading Romanian politicians on his side, this policy was not to the liking of the traditionally Francophile Florescu’s, who would continue to refer to the royal family as “the Germans”. As we have seen in my earlier chapter, Carol’s desire to renew the triple alliance had led to the dismissal of General Ioan Florescu as Prime Minister in 1882.

In particular, the situation of the Romanians in Transylvania had deteriorated during the nineteenth century as its Hungarian rulers realized that in an increasingly democratic age, the majority Romanian population, together with other ethnicities, posed a direct threat to the constitution of the state. Consequently, the twin pillars of Magyar policy at the time were the “magyarization” of the different ethnicities living under Hungarian rule, including the forcible adoption of Hungarian names and language, as well as the political unification of Transylvania with Hungary, in order to dilute the Romanian element. Thus the struggle for the rights of the Romanians in Transylvania acquired a cultural as well as a political dimension.

Alexandru Florescu, portret

Alexandru Florescu devotes his life to the plight of the Romanians in Transylvania

The member of the Florescu family who made it is his life’s mission to help the Romanians of Transylvania was Alexandru Florescu. The son of Dumitru, the romantic composer whose most famous composition is Stelutabased on a poem by Alecsandri, Alexandru was exposed early on to the ideals of the 1848 revolution which Dumitru fervidly believed in, as well as to Dumitru’s love of Romanian peasant traditions which is so evident in his music. Alexandru’s early life was difficult due to the premature death of his father when he was only fourteen, leaving his mother with five children to bring up (of their nine children, four had died prematurely). Short of money, she sold their Bucharest property and moved the family to an old Florescu property at Comisani, near Targoviste, the ancient capital of Wallachia, where the composer had been Prefect and then Mayor during the rule of Prince Cuza. Alexandru studied at the famous Saint Sava academy of Bucharest, and then together with his eldest brother was sent to continue his studies at the famous Lycee Louis le Grand in Paris, followed by the prestigious French Ecole des Mines. On his return to Romania, his aunt gave him an old “conac” (manor house) and an estate comprising several thousand hectares of forest and pastures at the foot of a mountain near the Dambovita River. This allowed him to lead a pleasant rural life, where he indulged in a passion for bear and boar hunting, which was to last the length of his life.

Alexandru tried various business ventures, including exploiting oil which had been found on his estate. A good shot, he even founded a shooting school at Baneasa, just outside of Bucharest. But none of these ventures met with much success, and his fortunes were only to improve significantly when he married Natalia Filodor, who came from a wealthy Greek family from Braila, at the time the centre of the Danube grain trade. Her father had been the Director of Russian quarantines on the Danube and a previous ancestor had been the commander of Prince Alexandru Mavrocordato’s army, whilst another had fled to Russia after the failure of Prince Ypsilanti’s Greek uprising. Natalia’s dowry was a large estate at Barlad in Moldova, which allowed the Florescu’s to settle into a comfortable life centred around a large house in central Bucharest. An extremely cultured man, Alexandru was hired by Prince Bibescu to give lessons to his son Valentin (who would go on to marry the famous writer, Princess Martha Bibescu), and he also acted as the Secretary to his uncle General Ioan Florescu.

With the backing of his uncle, It would have been easy for Alexandru to pursue a traditional career in politics, and he did eventually reluctantly agree to become the President of the Dambovita district council, where his Comisani estate was located. But he was disappointed in the politics of the time, and felt that the Romanian political class was ignoring the plight of its co-nationals in Transylvania. In 1882, Alexandru accompanied the King and General Florescu on a trip to Sigmaringen, where the King signed the original 5-year alliance with Austria and Germany, against the advice of the General. Meanwhile, the situation of the Romanians in Transylvania was deteriorating, and it was clear that the Nationality Laws of 1868, which were supposed to guarantee the rights of the different ethnic groups, were being abused. The Romanians of Transylvania responded by organizing a national party under the leadership of Ion Ratiu and Father Vasile Lucaciu (the latter was to become a life-long friend of Alexandru), and issued a plea to Emperor Francis Joseph to hear their case. But the Emperor returned the plea to the Hungarian Parliament unread, and the leaders of the Romanian National Party were tried and given a harsh sentence of thirty years’ imprisonment.

The League for the Cultural Unity of all Romanians

In 1895, one year after this so-called “Memorandum Trial”, Alexandru and a group of students and academics decided to form a society to support all the Romanians living outside the borders of the then Romanian state. It was known as the “Cultural League”, and it was ostensibly a society of cultural support in order not to create complications with King Carol, who had entered into an alliance with the Austrian Emperor. But in fact it was much more than that, for it was not possible to separate the cultural from the political when it came to acknowledging the rights of the Romanians in Transylvania, and its ultimate political aim was the union of all Romanians within a single state. Initially, the Cultural League’s activities took place in Bucharest, but shortly afterwards it opened branches all over Romania, as well as in major foreign cities such as Paris, Brussels, London and Rome, and it developed a more formal structure, with an elected President and a Secretary.

Alexandru Florescu acted as the League’s Permanent Secretary from its very beginning. His aims for the League were always political. In secret meetings, he regularly informed the King on the treatment of the Romanians in Transylvania, and in 1899, at a meeting of the Central Committee of the Cultural League, he revealed his true political objectives for the League:

“I appeal to whosoever is a true Romanian with courage and an honest conscience to follow the flag of the Cultural League”.

His speech was widely applauded in the press and shortly afterwards the League adopted the hymn “Romanians Awake” which is still sung as Romania’s national anthem. It was around this time that Alexandru established personal ties with the leaders of the Romanian National Party in Transylvania, inviting many of them to his Bucharest home on Calea Victoriei. The one he became closest to was Father Vasile Lucaciu, a Uniate priest, but his circle included the pioneer aviator Aurel Vlaicu, and Iuliu Maniu, who was to become the leading politician in Romania during the inter-war years. A special foreign friend and supporter was the great British historian R.W. Seton-Watson, who would later be consulted during the negotiations at Versailles which led to the creation of “Greater Romania”.

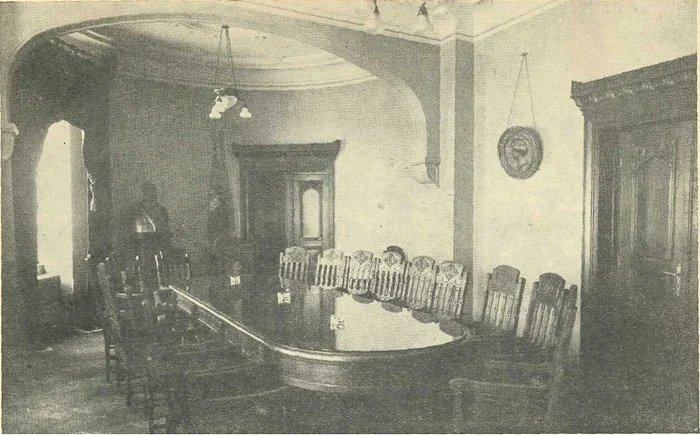

The Palace of the League for the Cultural Unity of all Romanians

It was during this period that Alexandru also starting making regular trips to Transylvania, in support of his friends and colleagues across the Carpathians. One of the main reasons was to take money to them, generally from his own personal resources (much to the distress of his wife), and it was rumoured that he had personally financed the defence of those being prosecuted under the “Memorandum” trial. But his visits did not go unnoticed by the Hungarian secret police, and an order for his arrest was issued. Alexandru promptly managed to cross the border and return to Romania using false identity papers, hiding books, pamphlets and large sums of money along the way.

Alexandru Florescu on a hunting party

In 1905, he travelled across Europe where he participated in various protest meetings at the treatment of ethnic Romanians by the Hungarian authorities, as well as a race congress in Brussels. It was partly due to this campaign across Europe that the attitude of the Hungarian authorities towards the Romanian leadership in Transylvania softened, and Budapest decided to release the sixteen remaining prisoners held under the “Memorandum” trial. The Romanian National party also adopted a more conciliatory approach, and sent a small delegation to the Hungarian Parliament, whilst Alexandru was allowed to resume his visits to Transylvania. His last visit as the League’s Permanent Secretary was in 1907, in support of his friend Father Lucaciu, who was running in a parliamentary election in Bihor county against a Hungarian candidate with powerful connections, who was supported by the Hungarian Prime Minster Count Tisza. Alexandru financed Lucaciu’s campaign for the seat, which he won against all odds.

But in 1908, the League decided to select a rival committee to run its affairs, and Alexandru was replaced as Permanent Secretary by the historian Nicolae Iorga, whose greater fame and international prestige helped raise awareness of the League’s work. Although Iorga later acknowledged Alexandru’s contribution to the activities of the League, his praise was not unconditional, and he described Alexandru as “a great patriot but far too romantic”. Iorga also considered Alexandru to be excessively French in outlook, and dismissed him as a “Bonjourist”. Even after losing his position, Alexandru continued to travel to attend international conferences where he spoke out for the rights and demands of the Romanians in Transylvania, as he did when he attended the First Universal Race Congress in London in 1911, together with Father Lucaciu.

World War I and the creation of Greater Romania

On 21 June 1914, one week after the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand and his wife in Sarajevo, Kine Carol I informed his ministers and the opposition leaders about Romania’s secret alliance with the Central Powers. The vast majority of politicians in attendance told the King unequivocally that Romania should remain neutral, and three months later Carol was dead, his death having possibly been brought forward by his distress at the knowledge that he had had to break his promise to his allies. Alexandru’s reaction to the death of the King was mixed. On the one hand, he respected the monarch as a man of principle who had patiently listened to his views on the treatment of the Romanian majority in Transylvania. On the other hand, he rejoiced at the fact that the alliance with the Central Powers had died with the King.

Two years later, Romania was at war with the Central Powers. Although the War started well, with the Romanians quickly penetrating Transylvania and occupying the city of Brasov, the situation soon took a turn for the worst once the German-Hungarian forces in Transylvania re-organized, and a simultaneous German attack from Bulgaria led to the fall of Constanta. The Romanian forces had to retreat to Moldavia, whilst the government was forced to abandon Bucharest and take refuge in Iasi. At this point the Florescu estate in Barlad turned out to be most useful, and the entire family took refuge there, where they were joined by Father Lucaciu. The situaton deteriorated further and in March 1918 Romania was forced to sign the humiliating Treaty of Bucharest, acknowledging its defeat and ceding part of its territory to Bulgaria. Eventually, Romania was persuaded to re-enter the War on condition that its allies offer it the same terms which had prevailed in 1916, and this time it was greatly helped by a contingent of French troops which landed in Salonica. Meanwhile Alexandru and Lucaciu stepped up their demands for unity with Transylvania, by establishing the National Council for Romanian Unity, which was recognized by the allied governments. In 1918 a council of Romanian Transylvanians met up in Paris, with Lucaciu and Alexandru attending.

Radu Florescu, dressed like a girl, and his small sister Elza

The complex negotiations at Versailles which ended World War One are beyond the scope of this article, but it is important to note that both Alexandru and Lucaciu were present at the sessions which led to the creation of Greater Romania, although they had no influence on the eventual outcome, which was left to a commission of “experts”. One of the consequences of Romania’s final victory at World War I was King Ferdinand making good his promise to the Romanian peasantry of a complete overhaul of land ownership, together with the introduction of universal suffrage. Thus a massive agrarian reform was brought about, with over 2 million hectares expropriated from the great landowners and distributed to peasant communities, and former landowners restricted to owning no more than 50 hectares of land. This reform represented the final economic death blow to Romania’s old aristocratic class, which had already suffered from Cuza’s agrarian reforms and, together with the rest of the European aristocracy, from a huge fall in the relative price of agricultural goods due to huge new areas of cultivation in Russia, Canada and the United States entering world markets. For the Florescu family, whose wealth had already been much diminished due to Cuza’s earlier agrarian reforms, these new reforms represented a harsh economic blow. And for Alexandru, who had devoted the bulk of his financial resources to the cause of the Romanians in Transyvlania, they meant that from now on he would have to live in much diminished circumstances. In spite of this, Alexandru and his family were strong supporters of the agrarian reforms, and a Florescu cousin was even challenged to a duel by a Filipescu relative due to the Florescus’ “betrayal” of the boyar cause (fortunately the duel ended in a stalemate, with both sides misfiring).

One avid proponent of the land reforms was Alexandru’s son Radu, who even wrote a book on the subject, entitled “For Romanian Justice:The cause of the Romanian peasant”. In this book, whose ideas were highly progressive even for the more liberal members of the Florescu family, Radu argued for generosity towards the peasant class. The book’s title page included the following subtitle:

“Generosity!

Genersoity is creative!

Our selfishness must be collective, not individual”

and in it he argued that, over the centuries, landowners had usurped the rights of the peasantry over the land by progressively increasing taxation;that society should not be based purely on capitalist individualism but that there should be greater solidarity between social classes which is indeed a legal and moral obligation;that the large landowners should only be compensated by the state for their loss of land by the minimum amount necessary not to affect the economic viability of creditor and debtor relations in the rural economy;that an income tax should be introduced to fund the expropriation;and that educating the peasantry should be a pressing priority for the Romanian state.

Radu was born in 1895 on the family estate of Comisani on the banks of the Dambovita RIver in 1895, where he had spent his early formative years together with his younger sister Elsa, before the family moved to Bucharest. The traditional patriarchal world of the Romanian countryside was one to which he would remain deeply attached for the rest of his life, even during his long years in exile after World War II. His mother Natalia Filodor was very keen that he receive a good education, and he was given early instruction in French and German, as well as, unusually for the time, English, whilst his sister studied sculpture under the well-known Romanian sculptor Friedrich Storck. He turned out to be a talented pianist, and was enrolled in the Bucharest Conservatory which his composer grandfather had helped set up, whilst he completed his studies at the Matei Basarab Lyceum. In 1913 he volunteered to serve in the Second Balkan War, and became a Lieutenant of the Third Rosiori Regiment, which was headed by Queen Marie.

When Romania entered the First World War in 1916, Radu saw active service as an artillery officer, and his unit was initially routed by the combined German-Hungarian Army, forcing it to retreat north to Moldavia. But when the Romanian army re-grouped in 1917, Radu’s artillery unit and his Rosiori cavalry regiment participated in some of the great Romanian victories of the War, including the battles of Marasti, Marasesti and Oituz. Towards the end of the war, Radu, who spoke fluent English, was asked by Queen Marie to act as an interpreter for an American Colonel who was working for the Red Cross in Moldova, helping to distribute food to soldiers and the famished local population. It was at this time that Radu developed a deep admiration for Queen Marie. He was then ordered to accompany the Romanian army to Bessarabia, which had detached itself from the newly-formed Soviet Union and decided to join the Kingdom of Romania. He wrote back a report on the conditions prevailing in Besssarabia, comparing it favourably to the war-torn region of Moldavia he had just left. His final war experience took place when Romania re-joined the war on the Allies’ side after the long-awaited French offensive from Salonica.

Radu Florescu

Radu Florescu enters the Romanian diplomatic service

After the War, Radu completed his studies in Barlad, where he wrote his book on agrarian reform. He then passed the bar examination, and took a temporary job at the National Bank of Romania. But his career started in earnest when he joined the Romanian diplomatic service. He was helped by his uncle, Nicolas Filodor, a life-long member of the Liberal Party and a close confidant of King Ferdinand (he had accompanied the King’s son Carol on his foreign travels), who worked as Permanent Secretary at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and had been the Romanian Minister in Athens and Belgrade. He was also encouraged to join the Romanian diplomatic service by his mentor and former Law Professor Nicolae Titulescu, who had become the Romanian Minister in London. Radu was soon to be named First Secretary at Romania’s legation in Prague, and then he became the Romanian Minister in Belgrade, before returning to Prague in 1927.

This was an intensive period for the Romanian diplomatic service. Whilst the outcome of World War I had been a triumph for Romania, with the newly formed “Greater Romania” having acquired Transylvania, a large part of the Banat and the Bukovina from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and Bessarabia from the Soviet Union, the new state was surrounded by countries which had lost territory to it. The Soviet Union, Hungary and Bulgaria refused to acknowledge their loss of territory and demanded revision of the treaties. Accordingly, the very survival of Greater Romania depended on the new international order which had been created after the conclusion of the First World War. Realizing this, all the Romanian governments of the interwar period pursued a foreign policy aimed at supporting the international order, including adhering to international agreements such as the Briand-Kellogg pact of 1928 which outlawed war as a means of settling disputes, the convention for the definition of aggression signed in London in 1933, and the pact of non-aggression and conciliation signed in Rio de Janeiro the same year. Romania also became a strong supporter of the League of Nations which was designed to secure the territorial integrity of all its members. Radu’s mentor Titulescu was himself named President of the League of Nations on two occasions.

Radu Florescu, in 1924, when his married at Sinaia with Vera Soepkez

Radu’s diplomatic posts took him to the two countries – Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia – which were, together with Romania, the main beneficiaries, and therefore the strongest supporters, of the international settlement brought about by the Treaty of Versailles. His main task involved consolidating friendly relations with these states, and during his term in Prague he got to know and respect the Czech President Thomas Masaryk and his Foreign Secretary Edouard Benes. He also developed a close friendship with Jan Masaryk, President Masaryk’s son. The outcome of the various diplomatic efforts of these countries was the creation of the Little Entente in 1920-21, whereby Romania, Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia, with the support of France, bound themselves to a common defence against Hungarian revisionism. On the domestic politics side, Radu remained a close associate of Ion Mihalache, who had joined the Peasant Party. Radu was delighted when the Peasant Party leader Iuliu Maniu became Prime Minister in 1928.

But after 1930, the situation took a turn for the worse, as Germany and Italy began to encourage active revision of the international order which was theoretically guaranteed by the League of Nations. Not only did this encourage the revisionism of Hungary, Bulgaria and the Soviet Union-countries which were strongly hostile to Romania – but Hitler’s ascent to power added a new dimension, because Germany coveted Romania’s natural resources for its war machine. Consequently, as Romania observed the rising power of Germany in continental Europe and the inability of France and Great Britain to offer meaningful guarantees for the security of its borders, its diplomatic efforts shifted. They were now focussed on “buying” German support for its territorial integrity by offering it economic concessions, in terms of privileged access to its cereal and oil resources.

Needless to say, Alexandru and his son Radu looked at the progressive collapse of the international order with profound sadness and dismay. With the creation of Greater Romania, Alexandru had felt that his life’s work had been achieved, but he had also lost a sense of purpose after its creation, and he was now becoming increasingly concerned about the decomposition of the international order which had been brought about by the Treaty of Versailles. It felt like an entire’s life’s work was under threat. His earlier work for the Romanians in Transylvania now largely unrecognized, he continued to work for a number of organizations aimed at preserving the status quo, such as the Anti-Revisionist League, the Anti-Hitlerite Association and the League of Orthodox Christians, up to his death in 1936.

The domestic situation in Romania was also becoming increasingly unstable. Romanians had been shocked when in 1927 Prince Carol had announced-for the second time-that he was abandoning the throne for the sake of the woman he loved, Magda Lupescu. His son, Prince Michael, became King at the age of six, and a regency was established. But the real problem was the growing political power of the mystic-fascist League of the Archangel Michael, which had been founded by Codreanu in 1927, and which was followed by the creation of the Iron Guard in 1930. Its origins can be traced back to the creation of Greater Romania, which brought about a de factomulti-ethnic state with large minorities of Hungarians, Jews and Germans, many of them urban dwellers economically much better off than that vast majority of the Romanian peasantry. Although the Agrarian Reforms and mass enfranchisement enacted after World War I had in principle improved the lot of the peasantry, it was difficult for the average farmer to scrape a living out of their small holdings, and the further division of land upon inheritance meant that it became absolutely impossible for the next generation to live off the land. There was mass immigration into the cities, where “foreign” ethnicities were often the dominant class, leading to resentment, and the situation was exacerbated after the crash of 1929 and the world depression that ensued. In 1936 Carol returned to the country, took over power from his son, and dissolved the Constitution and the traditional parties, and attempted to suppress the Iron Guard.

Radu Florescu observes Hitler’s rise to power in Berlin

During these years, Radu continued his diplomatic career outside the country. In 1931 he was named Counsellor in Berlin, where he was able to use his fluent German and knowledge of a country he had visited many times before, to report back on the growing threat posed by the Nazis. He attended a number of speeches delivered by Hitler and reported them back to Iuliu Maniu, including one at the Sports Palace in Berlin where he was heckled by Nazi sympathizers, and another one which he attended with the Romanian writer Panait Istrati. The legation’s main policy at the time was to support middle level German politicians, who wanted Germany to come to terms with its defeat and join the League of Nations.

Radu was delighted when in 1934 he was given the opportunity to leave the poisonous atmosphere of Berlin and take up a new post as Counsellor at the Romanian Embassy in Washington. Because of the long absences (and diplomatic inexperience) of the then Minister in Washington Carol Davila, Radu became the de factoAmbassador for most of the time he was there. Already a strong admirer of the American constitution and its way of life, he was delighted by the informality of diplomatic life in Washington. He sent back a number of reports to the Romanian government explaining the New Deal, the American Government’s desire to be on good terms with the Soviet Union, and the US’s shifting interest away from Europe towards the Far East. But upon his return to Washington from long absences in Europe, Davila was keen to regain control of the Embassy, and he arranged for Radu to be posted to Mexico City, where Romania had just opened a legation. Whilst Radu immersed himself in Mexican culture and history, the post was irrelevant from a diplomatic point of few, and Radu soon took steps to return to Europe. In 1936 he was made the Director of the Treaty Section of the Foreign Office in Bucharest.

The years spent in Romania turned out to be incredibly depressing. Hitler remilitarized the Rhineland in 1936, and the Spanish Civil War broke out the same year. In Romania, King Carol suspended the Constitution and started to rule the country directly. Meanwhile the Iron Guard started drawing up lists of politicians to assassinate. 1936 was also the year when Alexander died, whilst the much loved and respected Queen Marie was to die two years later. Having to deal with these depressing developments, Radu seriously considered abandoning his diplomatic career and devoting himself to farming the remaining lands he had inherited from his father in Barlad, Camineasca and Comisani. But in the Spring of 1938, he was surprised to be nominated Counsellor at the Romanian Legation in London. Suddenly, he was at the centre of a diplomatic storm.

Radu Florescu arrives in London to witness the start of World War II

Radu arrived in London at a critical time, shortly after Hitler’s annexation of the Sudetenland, which was done with the acquiescence of Great Britain. Later on that year, the Legation had to organize King Carol II’s visit to the Court of St James, which was an opportunity for the King and his Ministers to work out how much Romania could rely on British diplomatic, economic and military support after Hitler had started ripping apart the established order in Eastern Europe. Whilst the visit resulted in the British government extending loans for the purchase of some aircraft, torpedo boats and armaments, essentially it confirmed that Great Britain was resigned to German preponderance in South East Europe. Radu was soon joined by his old childhood friend Viorel Tilea, who was appointed Romanian Minister in London. From then on, the Legation’s main efforts were directed towards obtaining a guarantee from the British government of Romania’s borders of 1919. Although Chamberlain at a famous speech in Birmingham on 18 March 1939 talked about a dramatic change of policy toward Germany and hinted at defending Poland, Romania and even Greece, it was clear to the Romanian Legation that these declarations lacked any real credibility, and no formal guarantee was forthcoming. In his dispatches back to Bucharest, Radu suggested that British guarantees would only become credible if there were similar ones from the Soviet Union.

All changed with the Ribbentrop-Molotov agreement of August 1939, whereby Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union effectively carved up Eastern Europe, with Romania losing Bessarabia and its part of the Bucovina. King Carol was completely discredited, and in September he abdicated, handing the reigns of power to Antonescu who became the effective Leader (“Conducator”), whilst Prince Michael became the King in name only. Tilea was dismissed by the new government whilst Radu stayed on as Charge d’Affaires for a few more months, hoping that Romania would be able to remain neutral in the War. But he also chose to resign, conscious that Romania had effectively become a German pawn which was no longer acting as an independent country.

The beginnings of exile:Radu Florescu resigns in protest at Romania’s alliance with Nazi Germany

This act of defiance towards the Antonescu government ended Radu’s diplomatic career. All his properties in Romania were immediately confiscated by the regime, and overnight the family were considered traitors of their own country, whilst becoming enemy aliens in the United Kingdom, where they were threatened with deportation to the Isle of Man. But Radu’s resignation allowed him to disassociate himself from a regime which would go on to enter into a formal alliance with Nazi Germany, and to commit wide ranging atrocities against the Jews, in particular when the Romanian army re-entered Bessarabia and occupied Transnistria and parts of the Ukraine. As an admirer of the constitutional models of France and, above all, the United States, as a Romanian patriot, but above all as a man of culture and a humanist who had seen with horror the early development of Nazism at first hand in Berlin, Radu would not have been able to collaborate with the new Legionary State brought about by Antonescu.

To avoid the bombing of London, Radu and Tilea moved their families to a small village near Oxford, where they watched out the war develop from the sidelines. They suspected that Britain would end up losing the war, but believed in the justness of its cause. When Britain’s chances improved dramatically after the United States’ entry in the War, Radu started thinking about a new order in Europe after the defeat of Nazi Germany, and he wrote a number of pamphlets arguing for a federalized Europe along the American model as the best guarantor of world peace.

At the end of the War, his natural reaction was to seek to return to a “liberated” Romania. But friends in the British establishment who were well aware of Soviet intentions to take over the countries of Eastern Europe warned him not to. Indeed, Romania, which at the end of the war had the smallest communist party of any European country, was about to be thoroughly Sovietized, with anyone standing in the way of the new Soviet-backed regime thrown into prison or a labour camp, like the infamous Danube-Black Sea Canal, where thousands of political prisoners died. One member of the Florescu family who was not lucky enough to escape Romania was to spend eleven years in such a labour camp, but managed to survive the experience.

Because the traditional institutions of Romanian society and its economic infra-structure had survived the war remarkably well, the Soviets had to physically decapitate the old ruling class of Romania, including the independent judiciary, intellectuals, priests who took a stance against communism, and those politicians class associated with the traditional Liberal and National Peasant Parties. Radu and his family were deprived of the possibility to use their know-how, their values and skills to rebuild Romania after the war. But they were lucky to remain abroad. A number of other members of the Florescu family were stuck in Romania, where they were stripped of their properties, removed from their jobs, and their children, now considered members of an “unfit” part of society, had difficulty in getting access to a proper education.

Throughout the six hundred years history of the Florescu family in Romania, there had been a number of earlier exiles and confiscations of property, and in a sense the communist takeover was no different from prior invasions by more powerful neighbours.

But the communist takeover was to last longer and to have a much more profound impact on Romanian society, because of its totalitarian aim to penetrate every aspect of the country’s life, and because it lasted more than a generation. Furthermore, it was an invasion which was not based on reaching an accommodation with Romania’s traditional ruling class, as had been the case with the “capitulations” of the Ottoman period, the Phanariot penetrations of Romania in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and the repeated Russian occupations during the nineteenth century. Rather, it was an invasion whose aim was the physical destruction of that ruling class.

In barely one hundred years, Romanians had witnessed the triumphal achievement of the unitary state of Greater Romania, massive agrarian reform and the collapse of the old landed elites, the establishment of full scale democracy with universal suffrage, only to be followed by the tragic disintegration of the European order which had brought about its creation, followed by the dark periods of military dictatorship, fascism and totalitarian communism. But the country was to survive, slowly regaining its western, liberal and democratic orientation after 1989, in a painful re-birth after the traumas of a turbulent century.